In “The Wandering Thoughts,” the historian Jamie Kreiner exhibits that the battle to focus isn’t just a digital-age blight however even those that spent their lives in seclusion and prayer.

THE WANDERING MIND: What Medieval Monks Inform Us About Distraction, by Jamie Kreiner

Among the many sources which were plundered by trendy know-how, the ruins of our consideration have commanded loads of consideration. We will’t focus anymore. Getting any “deep work” carried out requires formidable willpower or a damaged modem. Studying has degenerated into skimming and scrolling. The one possible way out is to undertake a meditation follow and domesticate a monkish existence.

However in precise historic truth, a lifetime of prayer and seclusion has by no means meant a life with out distraction. As Jamie Kreiner places it in her new e-book, “The Wandering Thoughts,” the monks of late antiquity and the early Center Ages (round A.D. 300 to 900) struggled mightily with consideration. Connecting one’s thoughts to God was no straightforward activity. The objective was “clearsighted calm above the chaos,” Kreiner writes. John of Dalyatha, an eighth-century monk who lived in what’s now northern Iraq, lamented in a letter to his brother, “All I do is eat, sleep, drink and be negligent.”

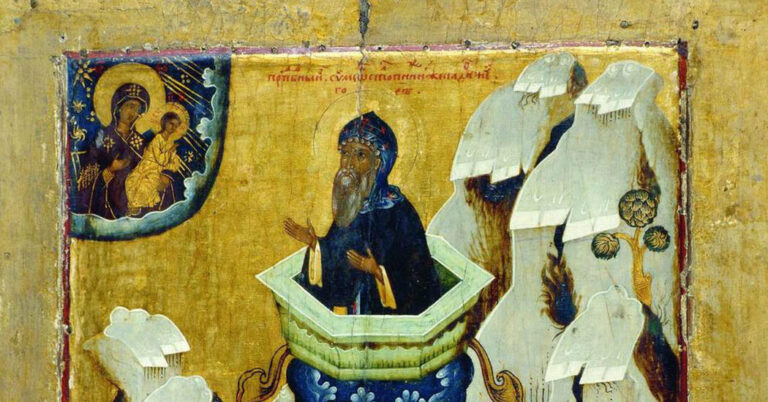

Kreiner, a historian on the College of Georgia, organizes the e-book across the numerous sources of distraction {that a} Christian monk needed to face, from “the world” to the smaller “group,” all the way in which right down to “reminiscence” and the “thoughts.” Abandoning the acquainted and profane was solely step one in what would grow to be an unrelenting course of — although as Kreiner explains, many monks continued to reside at residence, committing themselves to lives of renunciation and prayer. For the monks who did go away, there have been any variety of prospects past the confines of a monastery, which might pose its personal distractions. Caves and deserts have been apparent alternate options. Macedonius “the Pit” was a fan of holes within the floor. Frange dwelled in a pharaoh’s tomb. Simeon, a “stylite,” lived on high of a pillar.

Simeon was additionally recognized for resisting one other supply of distraction: the physique. Monks have been supposed to wish standing up, with their arms outstretched, to be able to fend off the temptations of sleep; Simeon took this exercise to such an excessive that even when one among his toes grew to become terribly contaminated, his powers of focus apparently by no means flagged. (Kreiner mentions an “exuberant metrical homily” that described, or maybe imagined, Simeon slicing off his personal foot and persevering with to wish whereas standing on his remaining leg, telling his amputated limb that they’d be reunited within the afterlife.) For the monk searching for oneness with God, the physique was an encumbrance. In any case, Kreiner notes, “angels have been pure consciousness.” Because the sixth-century desert father Dorotheos mentioned of his physique, “It’s killing me, I’m killing it.”

Not that such extremism amounted to a consensus view. Kreiner exhibits that monastic practices diverse broadly, reflecting a variety of views and disagreements. Nearly each exhortation to do one thing appeared to impress a warning to not take it too far. Elites who transformed to monasticism needed to be reminded of the necessity to costume shabbily and forgo the cologne, however “unkemptness might change into its personal distraction,” Kreiner says, with a monk “feeling useless about his griminess.” Just about the one level of settlement among the many monks in Kreiner’s e-book was a profound suspicion (at the least formally) of intercourse and sleep.

Books, too, have been double-edged, providing each distraction and clarification. They could possibly be edifying, providing monks a approach to take up sacred texts. They may serve extra sensible functions, stopping monks “from chatting in church earlier than the providers began,” Kreiner writes, in one among her characteristically congenial formulations. In fact, it mattered not solely what one learn but in addition how one learn. Monks have been inspired to learn slowly and methodically, and so they engaged with the textual content by writing notes within the margin. Kreiner says this marginalia helped them “to remain alert” — although she additionally concedes that typically what they scribbled down had nothing to do with the textual content at hand. A picture from a duplicate of Priscian’s Latin grammar features a word in Outdated Irish that reads lathaerit, or “huge hangover.”

Whereas the world might have represented “entanglement,” Kreiner writes, monks acknowledged a easy truth: “Distraction is inherent within the expertise of being human.” Ever since Adam and Eve the unity between humanity and God had been fractured. Kreiner says that the narrative of distraction and decline may be very outdated — far older than present anxieties over what the digital age has carried out to our brains. Even prayer, which was alleged to be “the best state of attentiveness,” wasn’t sufficient to crowd out different ideas. A monk may obtain the elegant stillness of revelation, however this was solely momentary, and within the subsequent second the thoughts would revert to its outdated distractible methods.

At one level Kreiner mentions that she has taught freshmen numerous “medieval cognitive practices” — together with meditation and mnemonic methods to visualise connections amongst tutorial ideas — to be able to assist them absolutely interact with what they’re studying of their different courses. The tactic “mainly quantities to high-level finding out,” she says, “however somewhat than being boring or intimidating, it’s adventurous and immersive.” Monks have been decided not solely to self-discipline the thoughts but in addition to work with it, accommodating a few of its foibles and idiosyncrasies, as a result of they noticed focus “as a matter of everlasting life and loss of life.”

Swap out “everlasting life and loss of life” for the tasteless mantras of “productiveness” and also you’ll get a way of how the stakes for monks have been fairly completely different from ours. The subtitle of “The Wandering Thoughts” is “What Medieval Monks Inform Us About Distraction,” which is a tantalizing, if considerably deceptive, proposition. This can be a charming and peculiar e-book. I can’t blame Kreiner for utilizing the cultural obsession with distractibility to coach our focus elsewhere, guiding us from the place to begin of our personal preoccupations to a larger understanding of how monks lived.

THE WANDERING MIND: What Medieval Monks Inform Us About Distraction | By Jamie Kreiner | Illustrated | 274 pp. | Liveright | $30

Adblock check (Why?)