Within the half-century because it developed from experimental movie within the Sixties, video artwork had an uneasy trip in museums, and never a single work attracted a really well-liked following. That modified in a single day in 2010, when Christian Marclay confirmed “The Clock”. Museum-goers have queued around the block in London, New York, Moscow and Melbourne to look at this mesmerising movie of movies, a 24-hour functioning timepiece composed of 12,000 clips marking each minute of the day, stitched collectively from greater than a thousand films.

“The Clock” received Golden Lion in Venice in 2011, and Marclay modestly thanked the jury for giving the work “quarter-hour” of fame. The work has now been well-known and beloved for a decade, however Marclay, a 67-year-old Californian-born, American-Swiss conceptual artist, is hardly identified past it. This winter’s retrospective on the Centre Pompidou is subsequently welcome and revelatory.

Starting along with his profession as a DJ, chopping up information to play in scratchy, jumpy sequences from the late Nineteen Seventies, and concluding with the premiere of “Doorways” (2022), his most charming piece since “The Clock”, the Pompidou explores the myriad idiosyncratic methods wherein Marclay has tried to convey music and the shifting picture into the museum, difficult concepts of what an exhibition might be.

He named his first music duo The Bachelors, Even, after Marcel Duchamp’s metaphor for erotic and artistic frustration “The Bride Stripped Naked by Her Bachelors, Even”, and within the brilliant “assisted ready-mades” dotted throughout the Pompidou’s ample galleries you instantly sense Duchamp’s affect.

A fantastical sculptural band consists of drum kits set on stems too excessive to succeed in; “Prosthesis”, an impotent pink silicon guitar drooping its neck; and — an particularly Duchampian thwarted picture — “Lip Lock”, a trumpet and tuba with mouthpieces fused in order that each are mute.

Marclay’s preliminary foray into splicing movie, in 1995, was “Telephones”, which rings out right here throughout a big open gallery, comedian and insistent. A seven-minute montage of rapid-fire hellos and goodbyes, it options actors in Hollywood films — Whoopi Goldberg with zebra-striped handset, Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart — as they dial, grasp up, stride to a cellphone sales space, cradle or smash a receiver, stare longingly at one which received’t ring.

Whimsically charming, swinging between humour and pressure, “Telephones” reduces narrative to absurdity, but unites its shards and remnants of dialogue into one bigger dialog, the ephemeral, ill-assorted characters related by movie’s tropes, gestures, gazes. The tone is nostalgic, intensified in the present day by the concentrate on applied sciences so shortly out of date — push-button and rotary dials, shiny Bakelite and brassy candlestick units, the kiosk on the finish of the lane, the scrabble for cash on reaching it.

The disparate voices of “Telephones” woven collectively right into a tapestry of acquainted babble inaugurated the strategy for all Marclay’s movie collages, which collectively type a disjointed comédie humaine. Though every is technologically extra complicated than the final, all are primarily based on the fragment, and the deconstructions learn as a mirror of a fractured society, with a push in the direction of concord within the reconstructed sequences, nonetheless strident the separate components.

You understand “Video Quartet” (2002) at first as a cacophony of staccato clips the place characters play an instrument, sing or shout, vehicles crash, tin cans hurtle down stairs and a roulette wheel whirrs loudly, declaring the factor of probability. These noises, interspersed with pop, punk, jazz, classical melodies, Jimi Hendrix and Elvis, Ella Fitzgerald and Maria Callas, Sam taking part in it once more in Casablanca, bounce between 4 screens to create an exuberantly dissonant musical-visual symphony. Marclay mentioned he labored “like a DJ, however with sonic photographs”.

Mixing, mashing, teasing out relationships between sound and picture, he chronicled the social media revolution from turntable to smartphone. The earliest collage is “Recycled Information”, sliced up vinyls from his DJ performances. “All Collectively” (2018) samples a whole bunch of Snapchats — footballs, fry-ups, fireplace engines. Picture overload intensifies within the intentionally bewildering “Subtitled” (2019), a stack of subtitle strips, alternating with photographs, shuffled on a loop. Sometimes completely different physique components incongruously line up, as within the surrealist sport beautiful corpse, or each part turns blue, or concurrently bursts into flame.

“Enjoying Pompidou” (2022), an interactive augmented actuality app, animates the constructing’s iconic facade into brilliant crimson, inexperienced, blue, turquoise strips. Every one corresponds to a colored column on the app, sparking offstage sounds — cranking raise, squeaky doorways — which Marclay calls “potential music”. If Duchamp is presiding godfather, experimental composer John Cage is simply behind. “Enjoying Pompidou” is a digital tribute to Cage’s composition 4’33”, consisting of ambient sounds in an in any other case silent live performance corridor.

It additionally pays homage to a constructing whose inside-out construction — multi-hued tubes, pipes, wires, escalators sweeping up the entrance — reworked museum structure within the Nineteen Seventies, declaring democratic, non-elitist intent. Marclay is at residence within the Pompidou’s playful multimedia milieu. “I turned the museum right into a musical instrument,” he says.

On this metropolis of Baudelaire, Marclay emerges as a Twenty first-century flâneur, portray fashionable life as it’s sampled, codified, memorialised on the moment. Displayed throughout ample excessive galleries boasting panoramic views of Paris, with turnings into darkish cinemas for among the movies, the present is a wandering parcours of broad areas, cul-de-sacs, points of interest, distractions.

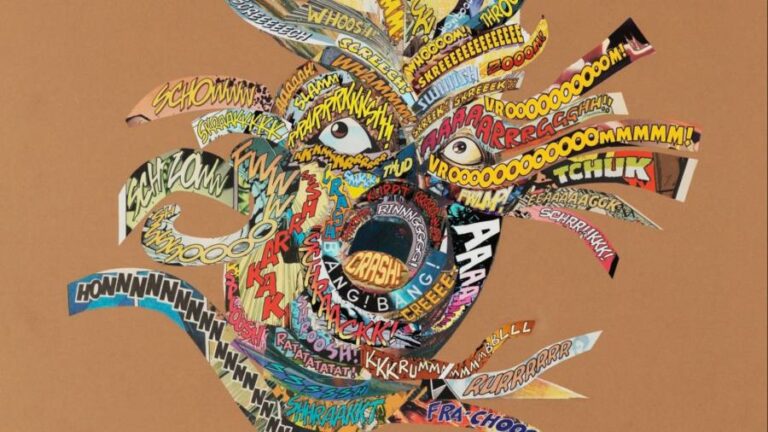

The 2-dimensional works really feel like avenue posters. The Actions collection, sound phrases — splash, swoosh, slurp — screened on to gestural work, mimics each summary expressionism and pop. The woodcuts of the Scream collection reprise Munch’s determine in scraps assembled from manga and cartoons, the shrieking mouth amplified by the wooden’s development rings, like sound waves.

Much less ingenious than the movie items, these nonetheless contribute to the “theatre of discovered sound” which enfolds us as we stroll throughout Marclay metropolis. The impact is immersive, seductive, but right here’s the surprise of the factor: “The Clock” isn’t there. And the Pompidou owns certainly one of its six editions. It’s a big omission, grievously denying the scope of Marclay’s achievement.

Compensation? “Doorways” is the present’s jewel. Drawing largely on Sixties classics — Alphaville, The Damned, Rosemary’s Child — it collages moments when characters open or shut doorways into an hour-long drama of transience and transitions. The passage by the door is the chopping level between every movie; actors rush by or slowly peer out, hesitantly finger the lock or fling themselves in opposition to the body, and presto! — one other individual and setting seems on the opposite aspect. As in “The Clock”, there’s a fluid dynamism, a hypnotic phantasm of continuity wrought from the disruptions, right here with an fringe of dread — the panic of the closing door, the nightmare of corridors and staircases main nowhere.

Marclay explains that he needed to “construct in individuals’s minds an structure wherein to get misplaced”. He has totally succeeded on this engrossing labyrinth of an exhibition.

To February 27, centrepompidou.fr