As a scholar of American evangelicalism, I typically spend my time writing and instructing concerning the overt beliefs and practices that White conservative Protestants make use of to additional entrench Christian nationalism and White supremacy as American values. White evangelicals are, for higher or worse, continuously saying the quiet half out loud. From their “segregationist theology” that turned upholding Jim Crow legal guidelines right into a biblical mandate within the Fifties to their wholesale rejection of crucial race principle as we speak, White evangelicals throughout the many years have actively upheld White patriarchy at each flip.

Certainly, racism and imperialism are such endemic options of conservative Protestantism that, all too typically, historians and political analysts alike mistakenly place them in opposition to usually left-leaning beliefs like secularism, feminism, and political and social liberalism extra broadly. However to take action is to disregard how racism and imperialism truly influenced the event of 20th century ideas of feminism and secularism, argues Gale L. Kenny in her new ebook, Christian Imperial Feminism: White Protestant Ladies and the Consecration of Empire. Kenny presents a historical past of White liberal Protestant girls’s engagement with multiculturalism and feminism from the 1910s by means of Nineteen Forties, arguing that imperial logics and racial hierarchy guided their embrace of Christian feminism at the same time as they rejected sure types of American imperialism and systemic racism.

Christian Imperial Feminism tracks the evolution of mainline White Protestant girls’s ecumenical organizations, beliefs, and practices by means of the early many years of the 1900s. On the flip of the century, White girls exercised their restricted authority within the church by means of gender-segregated mission societies, which concurrently offered them the chance to display familiarity with (and mastery over) different nations and cultures. Kenny argues that White Protestant girls’s missionary guidebooks and pageants “established cosmopolitan aesthetics and buildings of feeling” that formed their budding Christian feminist values.

By the Nineteen Twenties and Nineteen Thirties, many mainline Protestant church buildings had subsumed their women-run mission societies into all-gender (and normally male-dominated) organizations. White Protestant girls had been pressured to reevaluate their goals, and lots of of them selected to show their consideration to home Christianization as their new mission entrance. Throughout a time of heated schisms amongst fundamentalist and evangelical teams and amidst the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan rallying towards immigrants, folks of colour, Catholics, and Jews, mainline Protestant girls’s church councils more and more emphasised interdenominational, interreligious, and interracial cooperation.

Mainline Protestant girls’s organizations could have been more and more interracial and anti-nativist, however Kenny argues that the missionary impulse behind their “Christian Americanization” efforts betrayed its personal sort of imperialism. Such teams prolonged the hand of friendship to racialized European immigrants and new Black neighbors from the Nice Migration, however nonetheless characterised such teams as practising “ethnic” religions that would profit from the civilizing instance of White Protestant tradition.

It was inside this patronizing multiculturalism that White Christian feminism took form. White Protestant girls characterised different religions’ (and “ethnic” Christians’) oppression of ladies as endemic to their religion, whereas at the exact same time arguing that oppression of ladies by White Protestants was merely a misinterpretation of an in any other case liberating religion. Whereas White Protestants and religio-racial “others” might all profit from cultural alternate, White Protestant girls positioned themselves because the arbiters of such exchanges, reinforcing their very own beliefs, practices, and identities as normative and authoritative.

Maybe essentially the most beneficial perception of Kenny’s work is her identification of the politics of sentiment at play in White Protestant girls’s spiritual creativeness of the racial different. Early 20th century missionary pageants depicting Hindu or Muslim girls discovering liberation in Christianity, for instance, used racist tropes to additional the feminist goals of White Protestants by associating the “backwards” oppression of ladies with the racial and spiritual different. Christianizing and “liberating” these of different nations, then, carried out the emotional work of legitimizing White Protestantism as the perfect faith and tied girls’s liberation to White Protestantism.

Within the Nineteen Thirties and Nineteen Forties, as White Protestant girls sought to racially diversify their organizations, they typically centered on the religious advantages of racial and cultural alternate, centering their very own spiritual and emotional improvement. As Kenny writes:

Like enjoying a component in a missionary pageant, attending an interracial assembly generated an analogous thrill of inhabiting God’s various kingdom whereas additionally leaving the White participant assured in her superior Christian advantage and liberal cosmopolitan perspective.

Whereas these interracial efforts typically centered the advantages to (and experiences of) White girls, additionally they underscored White Protestantism as the one appropriately dispassionate enviornment for cross-cultural alternate. Kenny contends that historians should reckon with the lasting influence of White Protestant girls’s makes an attempt to “handle” race by means of the auspices of organized faith and the language of proto-second wave feminism. Such efforts helped form American conceptions of the secular—which Kenny specifies as “not the absence of faith, however what students outline because the means for governing faith.” In different phrases, she argues, “White Protestant girls’s work to outline permissible spiritual beliefs, feelings, and practices contributed to a largely Protestant-informed normative secularism in the US.”

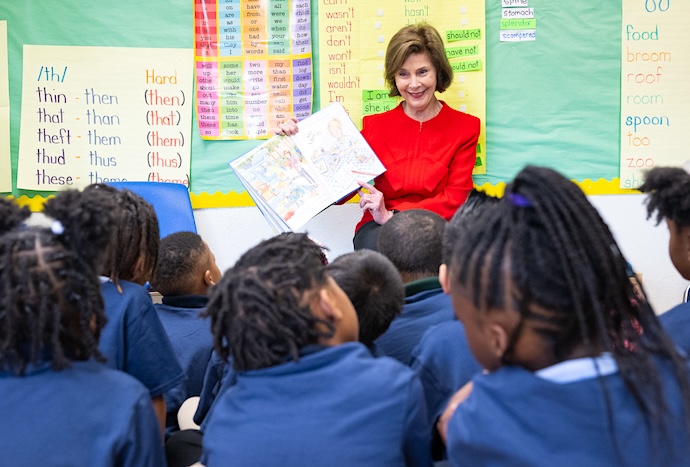

The persevering with affect of Protestant-inflected secularism that advances American imperialist targets by means of the language and emotional politics of White feminism will, maybe, come as no shock to anybody who’s ever learn a newspaper. Kenny briefly gestures at this actuality in her conclusion, drawing a through-line from early 20th century White Protestant church girls to Laura Bush’s 2001 radio deal with on the Taliban’s oppression of ladies in Afghanistan.

On this well-known speech, the First Girl contrasts the “brutal” Taliban with the misery and concern of “civilized folks all over the world,” ending with a name to People to be “particularly grateful for all the blessings of American life.” And but, in a single essential manner, Bush diverges from her Protestant forebears. Describing the Taliban as inimical not simply to Christian values, however to Muslim values, Bush says:

The poverty, poor well being and illiteracy that the terrorists and the Taliban have imposed on girls in Afghanistan don’t conform with the remedy of ladies in many of the Islamic world, the place girls make essential contributions of their societies. Solely the terrorists and the Taliban forbid schooling to girls. Solely the terrorists and the Taliban threaten to drag out girls’s fingernails for sporting nail polish.

With this rhetoric, Bush invitations Islam below the umbrella of what as soon as was characterised as a tri-faith America. And but, Islam is barely welcome on the desk inasmuch as People perceive it to comport with their very own imaginative and prescient of freedom and progress—a imaginative and prescient largely outlined by White Protestants.

Christian Imperial Feminism is, at its coronary heart, a strong historic account of mainline White Protestant girls and their shifting imaginative and prescient over the course of the primary half of the 20th century. The Civil Rights Motion, the Vietnam Warfare, and different home and geopolitical occasions would ultimately push some White Protestants to extra totally embrace anti-racist and anti-imperialist theologies and political stances, however Kenny rightly identifies the lasting affect White Protestant churchwomen’s Christian imperial feminism has had on normative understandings of American values as a common balm to girls’s oppression and religio-racial “backwardness.”

This sort of Christian imperialism is clear among the many vociferously rightwing: one want look no additional than Republican Senator Katie Britt’s latest rebuttal to President Biden’s State of the Union deal with, throughout which she positioned Chinese language communists and murderous unlawful immigrants as existential threats to “harmless People” counting on God’s steerage to realize their American dream. However the subtler, and maybe extra helpful, facet of Kenny’s work would possibly lie in its skill to encourage readers to contemplate how Protestant imperialist logic can even underlie extra progressive actions and organizations.

Adblock check (Why?)